Lightbeans Part 2, Sensors and Libraries

Often when we build devices we want them to react to the external environment. This means we have to implement some sort of sensor to detect the changes.

In this case we'll build a simple light detector.

To understand this circuit you will need a little electronics background.

We like current. Current gives power to lights, motors, speakers, and pretty much everything we need to run.

However, resistance is like the ogre that lives under the bridge. Every time somebody wants to pass, it requests a toll. A larger resistance means less current flows and the less bright our LEDs are. The exact equation is:

V = IR

However, a Light Dependent Resistor (LDR) is like an ogre that is afraid of light. The brighter it is, the smaller the resistance it has.

A tiny little problem here is that if we place an LDR in series with a battery, no matter how bright the environment is, the voltage will be 5V on one side and 0V on the other side. What if we wanted 3V on the other side?

Clues:

- You will need to wire up a LDR and a resistor

- Current in a series circuit is constant

- Voltage starts at +5 at one end and must be 0 at the other end

- Resistances add up in series

Well since we know that we can add up resistances, let's do that first.

R = R1 + R2

So imagine the entire thing is one giant resistor. Some current flows through it.

V = IR

V = I (R1 + R2)

But wait. Something interesting is happening here. We know V = IR . So this means that if we expand the equation...

V = I R1 + I R2 = V1 + V2

So the voltage across each resistor adds up to the total voltage. Now if the resistance of R1 increases, then this also means that V1 should increase. Now we have a relation between resistance and current! If we can measure the voltage across R1 (our LDR in this case), we can actually tell how much light is falling on the resistor.

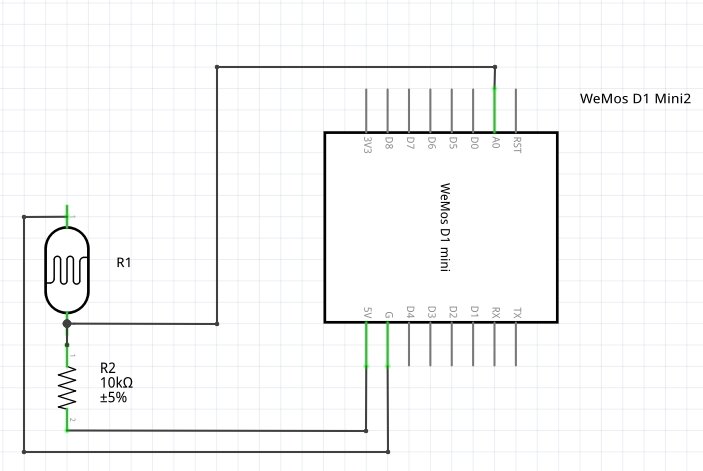

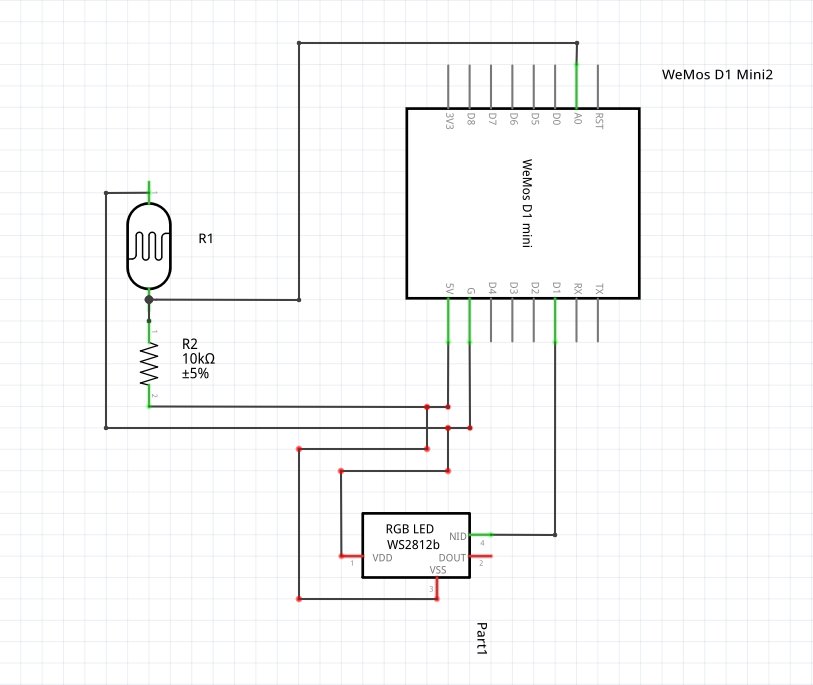

The brighter the room, the smaller the resistance across the LDR and hence a smaller voltage will be passed through it. Let's experiment with this by hooking it up as follows:

Figure 1. Schematic

The pin at A0 tells us the voltage after the LDR. Under brighter conditions, the resistance across the LDR falls and hence the voltage across the LDR falls accordingly and A0 reads a higher value.

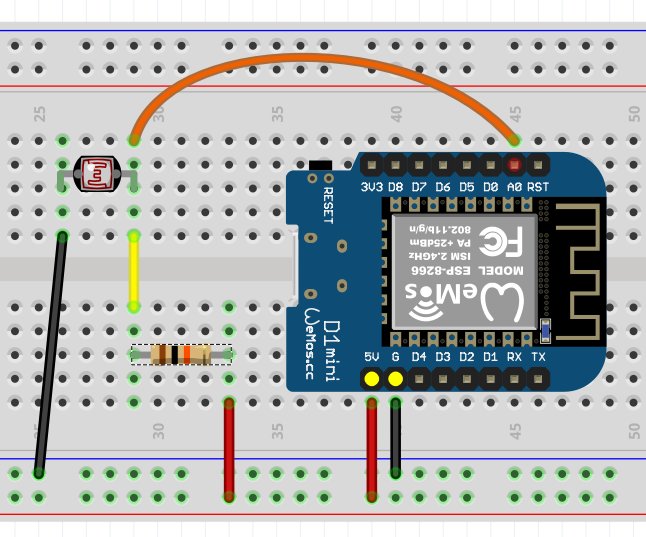

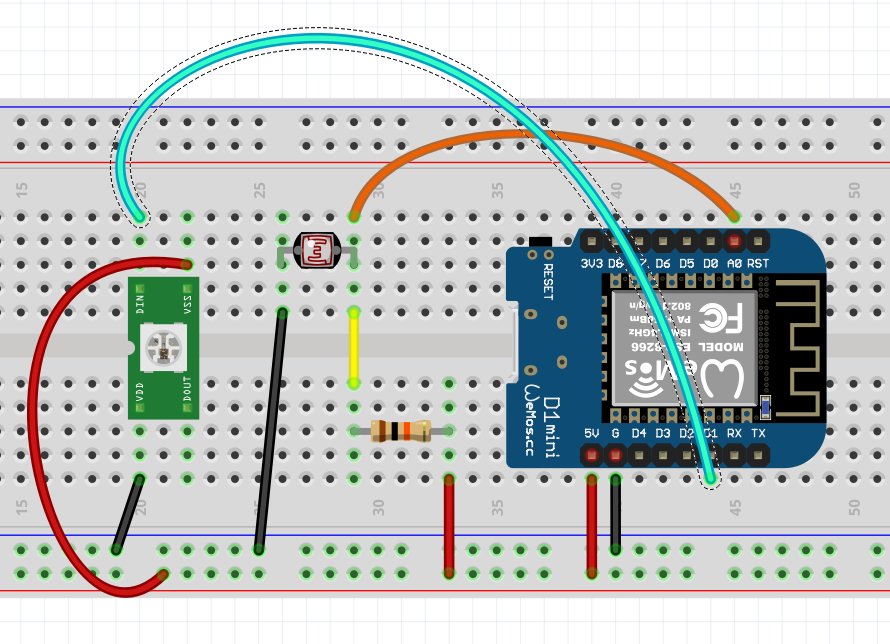

Figure 2. Wiring Diagram

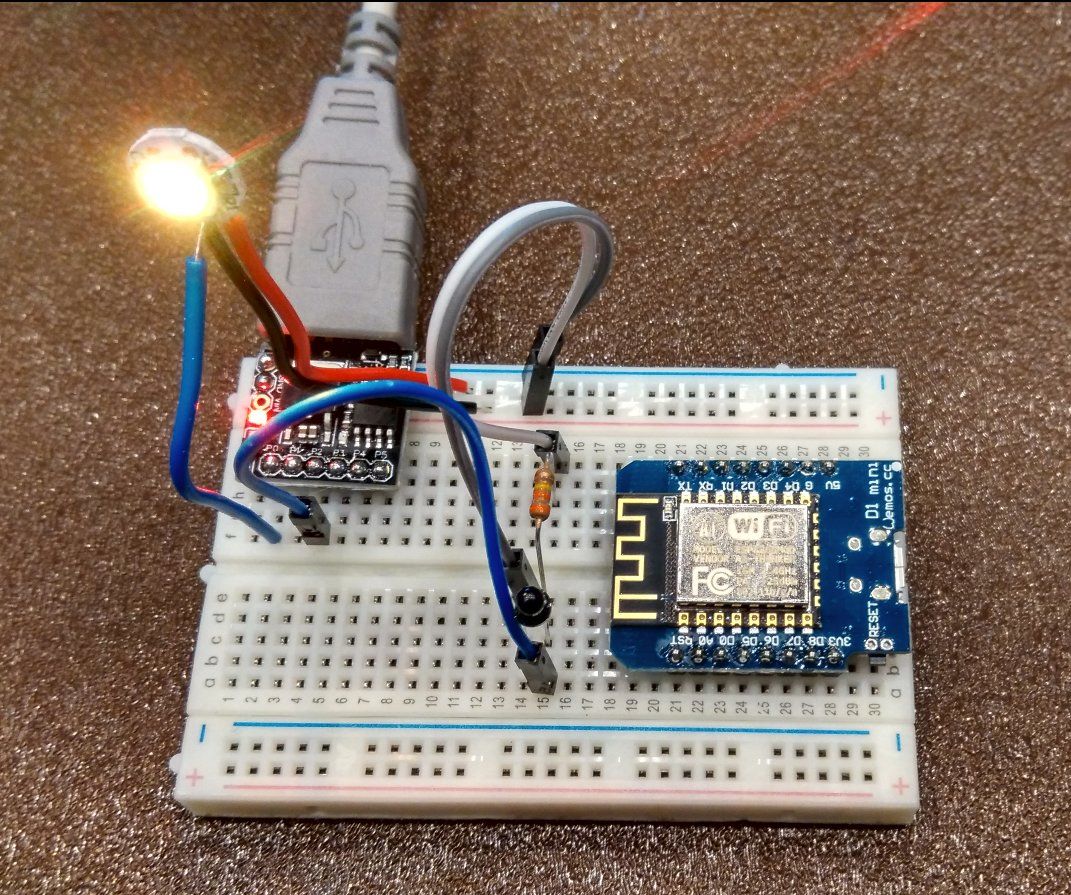

Figure 3. Wiring picture

If you flipped the position of the resistor and the LDR, the signal to A0 will then be flipped. It will read a low value in a bright setting, and a high value in a dark setting. Hence being able to estimate or determine voltages is very useful in predicting outputs and programming accordingly

Note that you'll have to scale depending on the brightness of the place you are using the circuit in. To get greater sensitivity in brighter settings, decrease the resistance in series with the LDR, and vice versa in darker settings.

Why are we using an analog input? Well since our other pins are digital, they can only sense if an input signal is HIGH or LOW. That is not in general very useful to us.

Programming

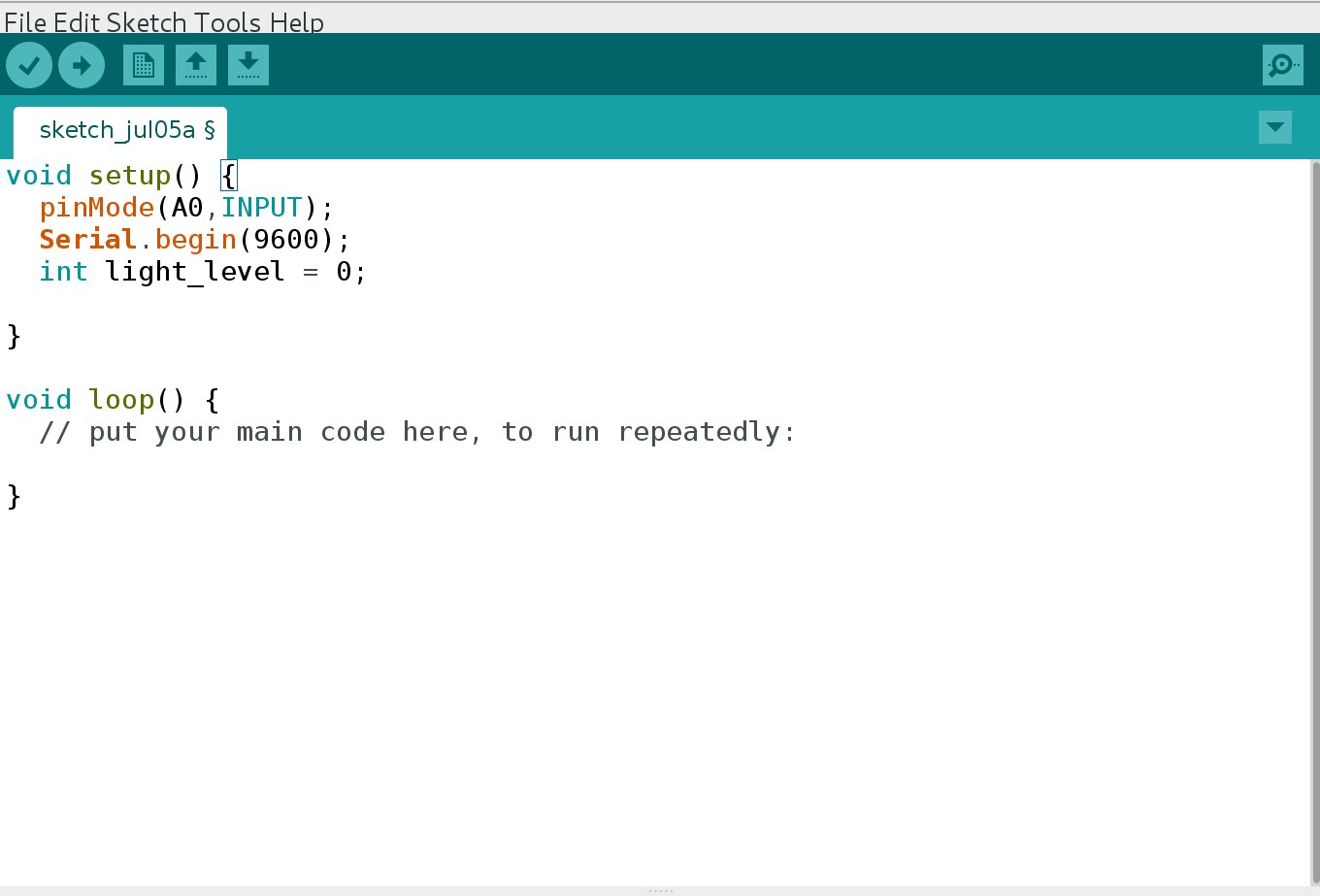

As usual we want to define our pins:

pinMode(A0,INPUT);

Now we want to use the Serial library to learn what our little sensor is detecting. A library in general refers to a set of programs or functions stored externally in a file, which you can use in your own program without having to write the programs or functions yourself.

This is sort of like visiting a library and pulling a book out to quote a line or copy an equation. So instead of having to write that entire book yourself, you can simply refer to the quoted material as "Book of Math, page 4, line 6". It is very convenient and this process makes for a cleaner program.

By default the Serial library is included, but not all libraries are, so sometimes we will have to define libraries. We'll not worry about that now, instead, within setup include:

Serial.begin(9600);

This sets up serial communications and the speed at which signals are sent is defined within the brackets. Now open the serial window by clicking the button at the top right corner of your Arduino program and check the 'baud rate' is the same as what you have defined. Sometimes if you receive gibberish in the Serial window, it is usually because the baud rates are different.

I wish to set up a constant to store my read values:

int light_level = 0;

int is an integer here, usually used for numbers. If you wanted to display a character, it would be char:

char my_word = 'd';

Now let's read our values and print them every second:

light_level = analogRead(A0);

Serial.println(light_level);

Serial.println("Println in action!");

Serial.print(light_level);

Serial.print("Print in action!");

delay(1000);

What do you notice? With println the output is printed on each new line while print prints on the same line. This is useful for formatting the output on the serial and other interfaces

Now if you shade the LDR, the values should drop and when you put it under light, the values should go back up.

Mawr LEDs!

Now we want to do something to this data we are getting. Looking back on our original LED program, can you come up with the final form of this project?

We want to write this value to the LED. Analog inputs are scaled from 0 to 1024, but our LED only scales from 0 to 255 so we need to modify this a little:

LED_value = light_level/1024 * 255;

However this only works if you have set up your LED such that the range is the full range. However my setup only went up to a maximum of 300, so the input was simply equated to the output.

LED_value = light_level;

To make it a little more interesting let's make our LED light up when it is dark:

LED_value = 300 - light_level;

The value of 300 was determined through a little trial and error. This is the largest value you should be able to read in your environment and setup. If the value you determined is too low, a negative value will be given to the LED and this essentially means that it counts backwards from 255, so you might actually see your LED suddenly become brighter after dimming!

Remember to define any new constants you use!

Sketch

int LED_value;

int light_level;

void setup()

{

Serial.begin(9600);

pinMode(A0,INPUT);

pinMode(D1,OUTPUT);

}

void loop()

{

light_level = analogRead(A1);

Serial.println(light_level);

LED_value = 300 - light_level;

analogWrite(D1,LED_value);

delay(10);

}

What you learned

- Analog inputs.

- Using sensors to drive outputs.

Libraries

In your package you might have a tiny white chip with three wires sticking out of it. This is a 5050 LED IC. What this chip does is that it combines three small but bright LEDs into a neat little package and by using some clever signalling, these LEDs can be made to shine at any level of brightness you desire and generating any color you want within the spectrum.

In this lesson, we will be using Adafruit's NeoPixel library which is available here. If you don't know how to install a library yet, the Arduino website provides a good guide to getting up and running quickly.

As described earlier, libraries are terribly useful and learning how to use them is very important. For this chip, it requires an extremely specific sequence of signals to be sent which is documented in a datasheet. Reading and writing such a function just to manage the LED would take up hours, but luckily, Adafruit has already done the hard work for us and we can use the functions they have wrote to assist us in our use of this device!

If you run across a device you'd like to use try searching online if there has been a library written for it. Chances are, it already has been done.

Programming

In order to use the library to run our pixels, we have to include it as follows (after installing it of course!):

#include <Adafruit_Neopixel.h>

Now we will introduce a new way of defining variables as follows:

#define NUMPIXELS 1

#define PIN D6 //connect to D6 of ESP8266

This is useful if you want to give a constant value to a name. Naming your variables adds clarity and simplicity to your program. Instead of having to change a variable in multiple places, you can now change it in a common place. So here we have defined D6 as the variable PIN. When the program is compiled, it will replace all occurances of PIN with D6. This compartmentalization will help in writing larger programs.

Next we want to set up our configuration for our 5050 chip. This should be included under setup.

Adafruit_NeoPixel pixels = Adafruit_NeoPixel(NUMPIXELS, PIN, NEO_GRB + NEO_KHZ800);

Now to break this down a little, Adafruit_NeoPixel refers to the type of value we are dealing with. This is similar to int or float. In this case, we are telling the IDE that "pixels" is a special structure that is defined in the library. It takes in a few variables, namely the number of pixels we are using and the pin number. We also have to specify the protocol, which we don't have to worry about in this instance.

Now when we want to use our LED, we merely have to refer to pixel.

The way we use the chip is that we define the colors first, and then we show them. It is like priming each pixel with a preset value before turning them all on simultaneously.

pixels.setPixelColor(0,pixels.Color(155,155,0));

pixels.show();

setPixelColor is a function that takes the the number of the chip in series you want to modify, and the color you want to modify it to as an RGB value. show takes no values and changes the color of the LED to the one you just defined.

Figure 1. Schematic

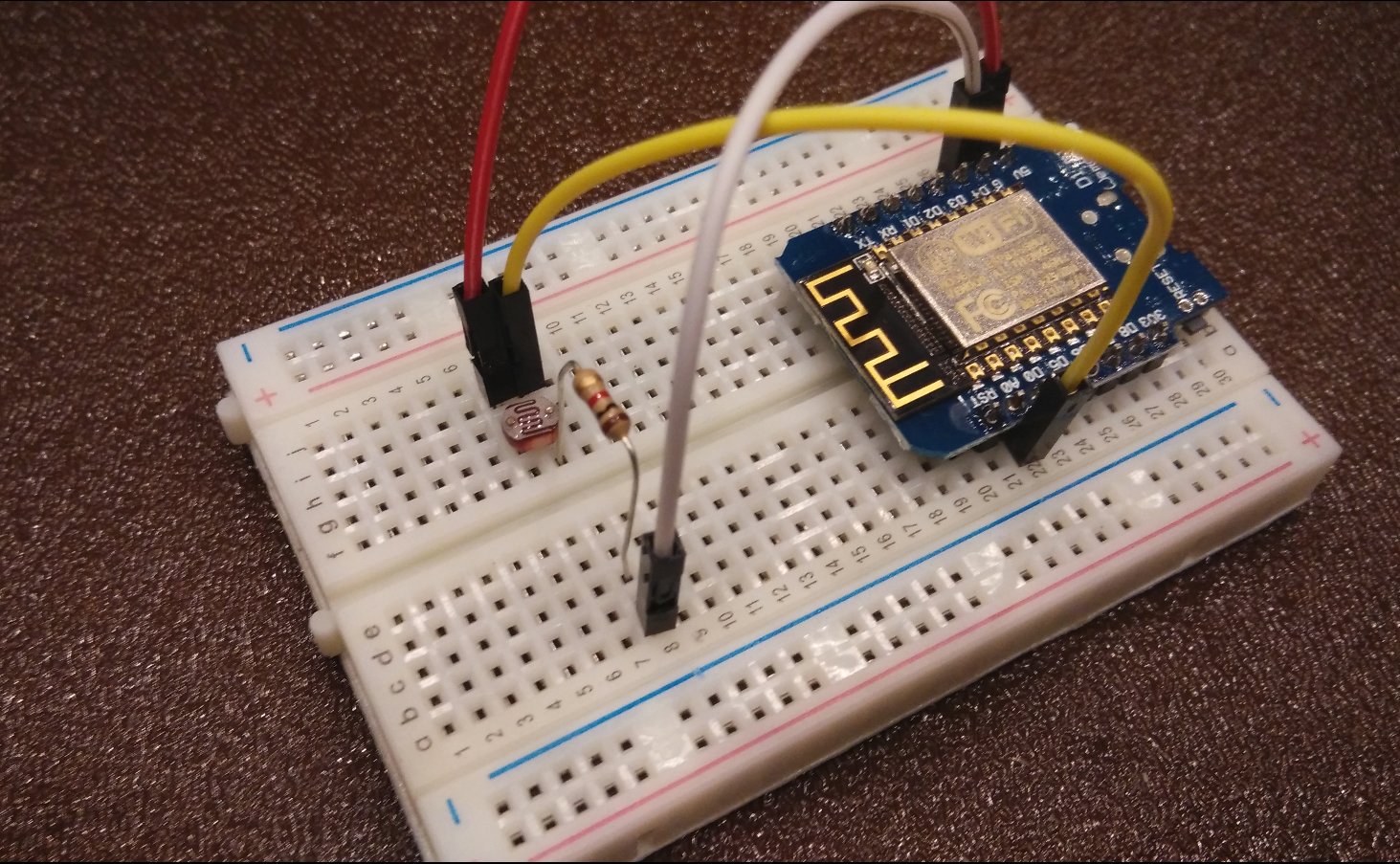

Figure 2. Wiring

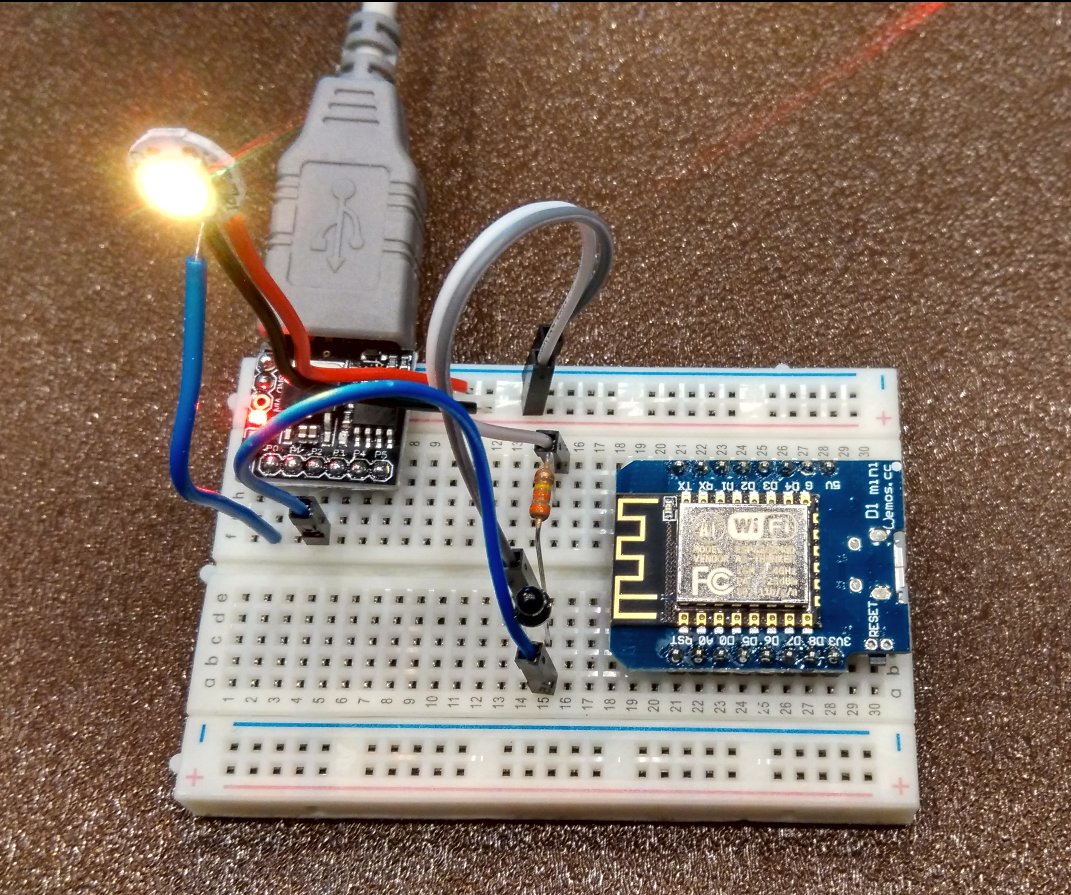

Figure 3. Wiring picture

Now you do something fun to scale the colors according to input. Knowing that each RGB value is from 0 to 255, we can use a linear scale from 0 to 765 to pick a color. Mixing two colors is more fun than having just red, green or blue, so as one color fades, we can make color brighten. Scaling our analog input to the range of 0 to 1023 (because this is the range of values that the sensor can read), we can then display a range of colors dependent on our input.

Figure 4. Lighting in action

Sketch

#include <Adafruit_NeoPixel.h>

#define NUMPIXELS 12 // Set this to the number of pixels you have

#define PIN D6

#define INPUT_PIN A0 // config for ESP8266

#define MAX_BRIGHTNESS 400.0

int r = 0;

int g = 0;

int b = 0;

float input_value;

Adafruit_NeoPixel pixels = Adafruit_NeoPixel(NUMPIXELS, PIN, NEO_GRB + NEO_KHZ800);

void setup()

{

Serial.begin(9600); // config for ESP8266

pixels.begin();

}

void loop()

{

input_value = analogRead(INPUT_PIN);

Serial.println(input_value);

input_value = ((MAX_BRIGHTNESS-input_value)/MAX_BRIGHTNESS) * (3*(255));

//Serial.println(input_value);

if (input_value<255){

r = input_value;

g = 0;

b = 0;

}

if (input_value<510 && input_value>255){

r = 510 - input_value;

g = input_value-255;

b = 0;

}

if(input_value>510){

r = 0;

g = 765-input_value;

b = input_value-510;

}

pixels.setPixelColor(1,pixels.Color(r,g,b));

pixels.show();

delay(10);

}

FAQ

- Help! My 5050 chip doesn't light up!

- Check that you are connected to the right pins and all leads are secured. Some unexpected values are caused by loose leads.

- Check that your resistor value is high enough. One way is to test the values in the

setup. If the resistor value is too low/too high the output will be 0 or 1024. - Check that you have put your photo-transistor in the right direction. The long lead of the photo-transistor goes to

GND.

- Help! It is still not working!

- Check for crossed leads and test the LED with a single value. If it still doesn't light up, your 5050 LED might be damaged, though that is usually unlikely.

Next Project

[Lightbeans 3](http://westsideelectronics.com/lightbeans-part-3-making-the-night-light-functions/)